The Trouble With Charlie...

‘Will any one of the children’s books written in the past thirty years be alive and beloved one hundred years from now?’ mused children’s author Eleanor Cameron (1912-1996) in an article in The Horn Book in 1972 that sparked a literary argument between herself and Roald Dahl that rumbled on for several months through letters to the journal.

Cameron described Charlie and The Chocolate Factory (1964) as being ‘one of the most tasteless books ever written for children; [but also], one of the best,’ adding:

‘The book is like candy (the chief excitement and lure of Charlie) in that it is delectable and soothing while we are undergoing the brief sensory pleasure it affords but leaves us poorly nourished with our taste dulled for better fare.’

Dahl was incensed describing her comments as vicious and nasty (he seemingly chose to ignore the slightly back-handed compliment). Charlie is dedicated to his son Theo who suffered a severe brain injury as a young child after his pram was hit by a taxi in New York City. In a reply to her criticism Dahl said ‘the thought that I would write a book for him [Theo] that might actually do him harm is too ghastly to contemplate. It is an insensitive and a monstrous implication.’

But Cameron’s main concern was the not violence visited on the juvenile miscreants touring Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory but the confectioner’s treatment of his workers. In a response to Dahl Cameron wrote:

I can only say that I find a certain point of view (or is it the lack of a point of view?) felt in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Knopf) to be extremely regrettable when it comes to Willy Wonka’s unfeeling attitude toward the Oompa-Loompas, their role as conveniences and devices to be used for Wonka’s purposes, their being brought over from Africa for enforced servitude, and the fact that their situation is all a part of the fun and games. I find it regrettable, too, that Willy Wonka, through the cleverness of his advertising, can triumphantly convince Charlie that life lived forever inside the factory, enclosed as in a prison, is the height of all possible bliss, with here again no word said, nothing expressed, that would question this idea.

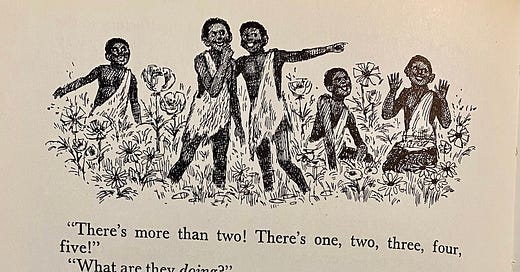

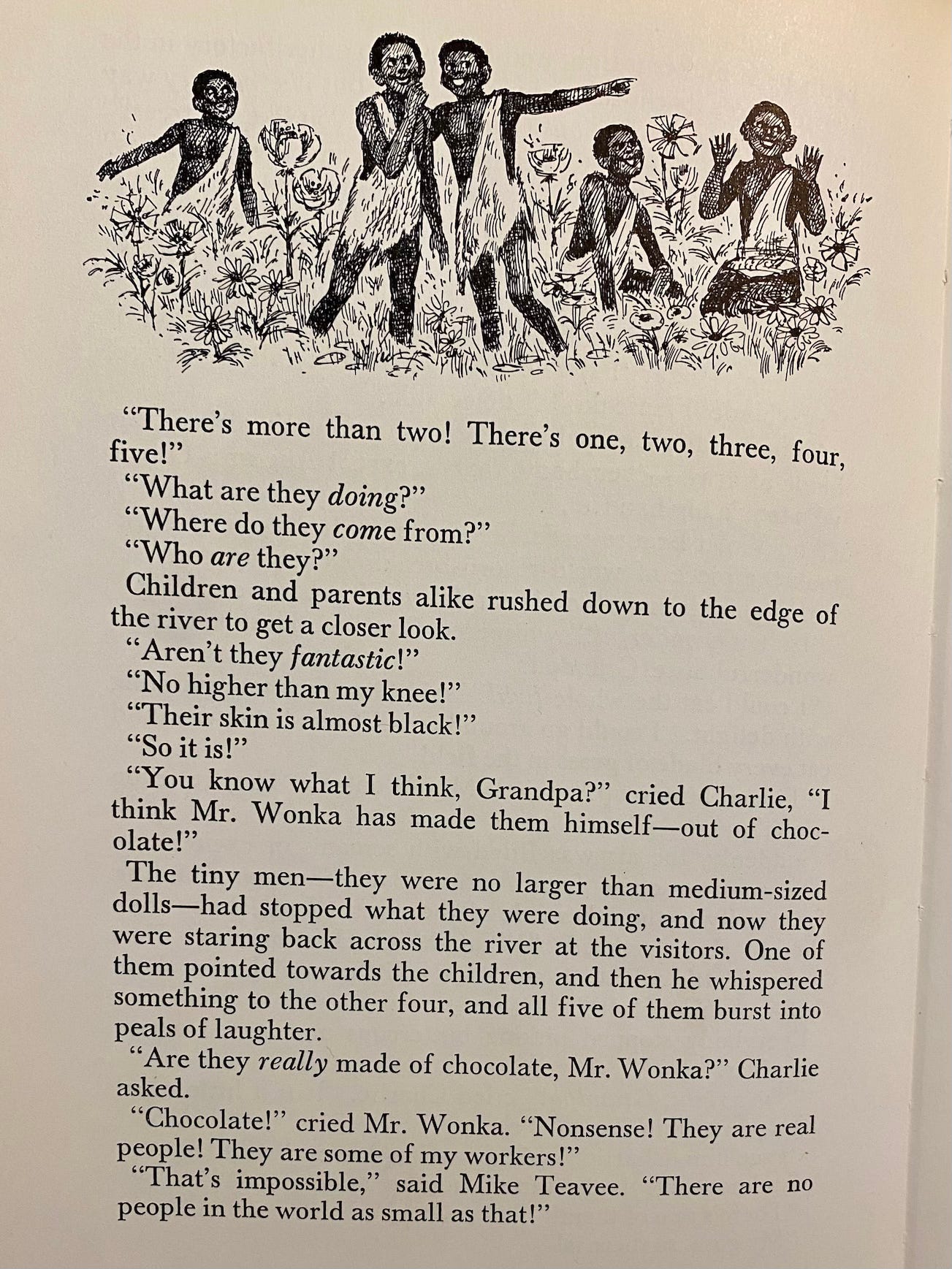

And this is the crux of the matter. Whether it was Dahl’s intention or not, the original published version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has racist connotations.

I smuggled them over in large packing cases with holes in them, and they all got here safely. They are wonderful workers. They all speak English now. They love dancing and music. […] They still wear the same kind of clothes they wear in the jungle. They insist upon that. The men, as you can see for yourselves across the river, wear only deer skins. The women wear leaves, and the children wear nothing at all.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1967)

The allusion to slavery is undeniable and although the Oompah Loompas are described as having rosy-white skin and long golden brown hair (amendments made with Dahl’s blessing) in more recent editions of this book, the passage above has remained in place.

According to Dahl’s biographer, Donald Sturrock, it had never been the author’s intention to cause offence with his description of the Oompah Loompas. When a film version of the book was slated in the late 1960s, The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) objected on the grounds that the Oompah Loompas reinforced ‘a stereotype of slavery that American blacks were trying to overcome.’ The organisation also wanted the name of the film changed to Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory to discourage sales of the book. Dahl agreed to the changes although Sturrock says that he described the NAACP’s attitude as ‘real Nazi stuff’ (Dahl could never be accused of embracing political correctness). Cameron’s article and subsequent retorts were merely poking an already very irate hornet’s nest.

There is an ironic twist to this battle. When Dahl conceived the story for the chocolate factory, Charlie was a black boy and the working title was Charlie's Chocolate Boy (Sturrock suggests that Dahl’s manservant Mdisho from his days with Shell Petroleum in Dar es Salam was the inspiration for this character). There were no Oompah Loompas and no references to Africa. On the tour of the factory Charlie is unwittingly encased in chocolate and sent, in moulded form and unable to speak, to Wonka’s house where he witnesses a burglary. Once liberated from his chocolate cast he is able to identify the robbers to the police and is rewarded by Wonka with the biggest chocolate shop in the world. But the publishing world was not convinced that a black hero would sell books and Dahl was advised to revise his story. And so Charlie became a poor, hungry, white kid and Willy Wonka a slave owner by any other name.

In the early 1970s Cameron railed against Herbert Marshall McLuhan (1911 – 1980), known as the father of media studies, who appeared to be of the opinion that television would be the death of books. To Cameron books were important to the very fabric of society and she stressed the importance of reading to children to ensure this state was preserved. Cameron would be relieved to know that books are still being published although you can now order them on line and read them on a screen. There have doubtless been many authors, children’s or otherwise, who have faded into obscurity over the past six decades but Dahl is not one of them (sorry Cameron!). I’d wager that forty years from now children will still engage with his books in some form so Dahl’s creations will live on.

Useful Links

You can hear the episode I recorded with Dr Allie Pino and Vanessa Baca on the horror elements of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and the movie spin-offs here.

You can read Cameron’s articles and the correspondence between herself, Dahl and others on the Horn Book website. However, you can only access a certain number of these a month free of charge.

‘McLuhan, Youth and Literature. Part 1’ by Eleanor Cameron in The Horn Book, 19 October 1972 (this is the original article that sparked the argument with Dahl)

‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Reply’ by Roald Dahl in The Horn Book, 27 February 1973.

‘A Reply to Roald Dahl’ by Eleanor Cameron in The Horn Book, 19 April 1973.

Many people agreed with Cameron’s view of Charlie and the Chocolate factory including fellow children’s author, Ursula K Le Guin.

Catherine Keyser unpicks a lot of the issues outlined above in ‘Candy Boys And Chocolate Factories’, Modern Fiction Studies Vol. 63, No. 3 (Fall 2017), pp. 403-428

‘Can Censoring A Children’s Book Remove Its Prejudices?’ by Philip Nel, on philnel.com 19 September 2010

Storyteller: The Life of Roald Dahl by Donald Storrock London: Harper Press, 2010

Dahl’s name still courts controversy to this day: ‘What to Know About Children’s Author Roald Dahl’s Controversial Legacy’ by Megan McCluskey on time.com, 23 February 2023